Back to History & Archaeology

History of the palace

The palace of Dukes of Brabant

Perched on the Coudenberg and dominating the town, the Palace of Brussels was without a shadow of a doubt one of the most beautiful princely residences in the whole of Europe. It traces its roots back to the 12th century. In the 13th century, the Dukes of Brabant decided to give the city a central political role. In the following century, this defensive castle soon became a mecca for diplomats and a prime site for entertaining.

Perched on the Coudenberg and dominating the town, the Palace of Brussels was without a shadow of a doubt one of the most beautiful princely residences in the whole of Europe. It traces its roots back to the 12th century. In the 13th century, the Dukes of Brabant decided to give the city a central political role. In the following century, this defensive castle soon became a mecca for diplomats and a prime site for entertaining.

When the Duchy of Brabant fell into the hands of the Dukes of Burgundy and more specifically Philip the Good, the city of Brussels endeavoured to attract these rich princes – the most profligate spenders of the age – to stay within its walls. To this end, the city constructed a prestigious state banqueting hall – the Aula Magna – between 1452 and 1460.

The successor of the Dukes of Burgundy – Charles V, the most powerful Western emperor – personally oversaw the development of the palace during the first half of the 16th century. An imposing chapel in the Gothic style was built during his reign.

The palace’s other wings did not lag behind: the main building was also enlarged and elevated, new windows were added, and a vast gallery decorated with statues was erected. This ample complex was transformed over the centuries in the Brabantian, Burgundian, Spanish and Austrian style as each sovereign was intent on making his own mark. Highly refined works of art graced the apartments including the most delicate tapestries and embroideries, sumptuous silver and gold objects, luxurious illuminated and printed books, sculpted statues and busts and the finest glass and china work, without forgetting countless paintings by renowned artists such as Titian, Rubens and Brueghel.

The fire of 1731

On the 3rd of February 1731, after a tiring day, the Governess of the Netherlands, Marie-Elisabeth of Austria, retires to her apartments in the palace of Brussels. Overcome with fatigue, the sister of the Emperor Charles VI fails to extinguish the candles. The fire quickly passes through wooden panelling into adjacent rooms.

On the 3rd of February 1731, after a tiring day, the Governess of the Netherlands, Marie-Elisabeth of Austria, retires to her apartments in the palace of Brussels. Overcome with fatigue, the sister of the Emperor Charles VI fails to extinguish the candles. The fire quickly passes through wooden panelling into adjacent rooms.

Throughout the night, the palace guards struggle to extinguish the blaze with the only means at their disposal at the time: leather buckets and water spray pumps. The town militia who gather quickly to help are pushed back in the confusion. The strict respect of protocol, formally forbidding access to the governor’s private apartments, prevents the fire fighters from attacking the source of the blaze. The governess is saved by the intervention of a grenadier who dares to break down the doors of her apartments. In addition, the wind is strong and icy conditions hamper water supplies.

From reading the investigation report, it appears that the witnesses didn’t dare to directly accuse the signora Capellini, the Governess’ maid and one of her favourite companions, but that they nevertheless thought her guilty. The findings of the investigation aimed to protect the Governess by establishing that the fire had originated in a kitchen located underneath her apartments, where a banquet was being prepared.

The Royal Quarter of the 18th century

After the drama of 1731 that left half of the palace destroyed, the Court moved to the neighbouring Nassau House, which served as the future palace to Charles of Lorraine. The ruins of the palace were left almost completely abandoned for forty years and were nicknamed the “Burnt Court”.

After the drama of 1731 that left half of the palace destroyed, the Court moved to the neighbouring Nassau House, which served as the future palace to Charles of Lorraine. The ruins of the palace were left almost completely abandoned for forty years and were nicknamed the “Burnt Court”.

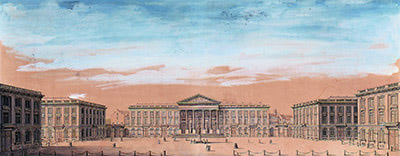

In the 1770s, political will and financial conditions met around a large-scale architectural project to redevelop the entire court district. The ruins of the old palace as well as numerous surrounding buildings were raised to the ground in order to make way for the creation of a new square: Place Royale. The square was to be bordered with neo-classical buildings, that can still seen today.

As for the park and the numerous gardens of the palace, they have been replaced by a neo-classical park and the Coudenberg's former slopes have disappeared from the urban landscape.

Certain elements of the old buildings were nevertheless preserved to function as cellars and foundations for the new constructions. It is these remains that we can visit today at the Coudenberg archaeological site.